Art of the Scare

How two Bay Area animators hope to revolutionize Saturday-morning TV

|

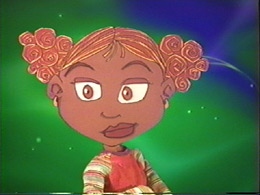

Fortunately, Mrs. Oglesby isn't real. She's an evil foil for the seventh-grade ghostbusters starring in a new animated children's television show produced and set in San Francisco. But before she can star in Phantom Investigators -- which has its national debut this summer on the WB network -- Mrs. Oglesby needs some repair.

"Can someone get me a glue gun?" series co-creator and director Stephen Holman shouts to a passing assistant as he operates the frightening puppet with one hand and holds a broken piece in place with the other.

Holman's solution is decidedly low-tech at a time when computer-generated animation rules. This is, after all, the land of the pioneer Pixar Animation Studios. In fact, Holman's entire show is old school. With Phantom Investigators, a determined band of purist craftspeople and artisans is attempting to create the next cool thing with nary a pixel or mouse click. Tossing computers aside, they combine labor-intensive (i.e., expensive), hands-on methods like stop-motion animation, puppetry, and scale-model sets with some live-action performances to create a unique product. The end result, they believe, is more rewarding, beautiful, and real for the effort. But will the target audience of 6- to 11-year-olds, weaned on simplistic cell-animated cartoons and computerized blockbusters like Monsters, Inc., really care?

Holman and his co-director, Josephine Huang, think so -- and they've got deep-pocketed backing. This funky husband-and-wife team (she's hip, he's subversive, and they're both obsessed with animation) convinced Hollywood conglomerates to take a risk on the stop-motion style.

"We're an oddball little company that beat the odds," Holman says.

"Yeah, a lot of industry people are surprised and perplexed," Huang agrees. "They don't see what we do as very practical or smart for business."

For the sake of their art (not to mention their continued employment), Phantom Investigators' creators hope it will be a hit. So does Sony Pictures Family Entertainment, which is bankrolling the show. The WB network does, too. With the highest-rated Saturday morning lineup on TV, it can't afford to waste a precious time slot on a dud. Even fast-food chain Carl's Jr. has an interest, hoping its Phantom Investigators toys (released before the show's debut, due to a timing glitch) will sell more kids' combo meals.

To offset the financial risk and keep it in production, the program must succeed after just a few weeks on the air: Companies that bet big money on an experimental show generally move quickly to the next idea until there's a win. This means that with the initial order of 13 episodes nearing completion and the premiere in sight, everyone involved with the show has reason to fear Mrs. Oglesby's toilet plunger.

|

"Phantom Investigators is not a super-serious, Buffy-style, superhero fight fest," Holman tells his writers in a memo. "This is a fun show. We should parody horror as well as provide genuine scares and thrills."

The point of the show is to defy the decades-old children's TV formula of corny slapstick and mindless action, as seen in numerous cartoons from Casper the Friendly Ghost to Mighty Mouse to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Holman and Huang hope that the show's visual uniqueness and its unconventional content will grab the attention of ever-more-sophisticated young media consumers. They realize that what worked for them when they were kids would fall flat today.

For starters, they don't promote the idea -- endorsed on children's mystery shows like Scooby-Doo -- that the supernatural can all be explained away. The ghosts in Phantom Investigators are real.

"We tell kids there is more to life than meets the eye. There will be no dull, rational explanations that spoil the fun," Holman says. "In our series, adults -- a metaphor for closed-minded mentality -- cannot see the ghosts, but open-minded children can."

|

Phantom Investigators uses San Francisco's storied history as a backdrop. The show's plots conjure up all kinds of ghosts from bygone eras: Gold Rush 49ers, 1906 earthquake victims, Alcatraz prisoners, Haight Street hippies, even Internet and venture capitalist demons.

"San Francisco is a funky town. It's a great Gothic City with so many fun little places -- the Sutro Baths, Coit Tower, Twin Peaks -- that can provide graphically and aesthetically pleasing scenes," Huang says. "Our stories will be a little bit of fantasy and a little bit of history. As long as there is some reality to the show's spine, we can get as wacky as we want."

At the peak of production in January, Custer Avenue Stages was a veritable stop-motion beehive. Heavy black drapes divided the giant sound stage into 30 mini staging areas where animators simultaneously filmed as many different scenes. Cameras rolled as employees maneuvered puppets across fantastical model sets, such as Mrs. Oglesby's creepy nether-realm home. In other areas, carpenters feverishly sawed, hammered, and glued sets to keep up with the shooting schedule, while puppet-makers sewed and stitched.

Stop motion's limited technology is what makes the results so interesting to look at -- and so difficult to achieve. Wood, metal, or clay puppets are moved by hand in what can be clumsy ways, giving the medium its delightful three-dimensional appearance. And while cell animation is also time-consuming, its method of drawing each frame is quicker and more fluid than the intricacies of stop motion.

To bring it all to life, Huang hired local stop-motion veterans like Tim Hittle, whose film Canhead received an Academy Award nomination for best animated short in 1996.

Hittle must continually position and reposition his puppets for every fraction of a second filmed. The children's facial expressions alone are daunting: He has to rearrange hundreds of little eyes, mouths, and eyebrows -- signifying every possible emotion from joy to despair -- on the puppets' faces for every shot. Because everything must be filmed in sequential order, one mistake can jeopardize an entire day's work, causing a noticeable hiccup in continuity. In stop motion, there's

"Stop motion is a lot like live theater, or a tightrope," Hittle says. "It's easy to get safe and bored on a computer if you're not careful. Stop motion is definitely riskier. It's intuitive. You have to

make choices all the time and live with your mistakes -- just like real life. It's more nerve-wracking, but you kind of rise to it."

|

"Everybody's blue jeans are his plaid pants," Huang says. Meanwhile, her costume consists of 4-inch-long dangling silver earrings, shirts graced with Lichtenstein pop art prints, glittery jeans, and no less than half a dozen mini butterfly clips on her head to create an explosion of hair.

The two come from very different places, and almost a decade separates them in age. Holman was raised in England's quiet countryside and listened to the Sex Pistols as a teenager, eagerly joining the English-led punk rock rebellion. "There were skinhead punks and art-school punks," he says. "I was of the art-school variety." He'll be 40 this year. Huang, 30, was born in Taiwan, but spent her childhood attending an art school in Toronto that was Canada's real-life version of the movie Fame.

Despite their differences, they share a passion for stop-motion animation, which brought them together both professionally and personally. Holman spent his 20s doing experimental theater in New York -- "Surreal, messy, cabaret-like theater complete with giant rabbit suits," he says. He ended up working for the infamous kids' TV show Pee-wee's Playhouse, where he used a combination of cell animation and stop motion to bring Pee-wee's black velvet paintings to life. That job led to work on MTV's edgy animated shorts, Liquid TV, in the early 1990s.

Huang took a more direct route, interning on the 1993 stop-motion film The Nightmare Before Christmas before becoming one of the main animators for James and the Giant Peach two years later.

The animation world was small when they met and fell in love almost 10 years ago. They married and formed their own animation company, Wholesome Products.

""Wholesome Products' is a running joke," Holman says. "It's our way to sound more squeaky-clean now that we're in kids' TV, after having done so much underground work."

Their first endeavor together was Life With Loopy, a series that aired on the children's network Nickelodeon for four years in the late 1990s. Its quirky mix of stop-motion animation, live-action hand puppets, and marionettes -- not to mention its popularity -- made the industry take notice. The result was that Holman and Huang found it increasingly easier to get meetings and pitch their ideas.

As a team, they make a good match. He has lots of ideas and she has the technical know-how to make them happen. They're constantly together, yet have thus far spared the crew from any obvious meltdowns. "It's very bizarre -- we seem to be able to exist like that," Holman says. "We have squabbles, but we learn to forgive each other a lot. We really do complement each other's strengths and weaknesses."

For example, Huang adds the hip factor.

"I always worry that what I like won't translate to kids today," Holman says. It's not that he's too old at 40, but that his tastes lean to the weird. "A hit show needs to be cool, not weird. If kids are turned off by your weirdness, you're sunk."

He explains, "I come from this highfalutin place, full of theories ..."

"... and I'm more fascinated by pop culture," Huang adds. "I still watch a lot of MTV. Am I just trying to hold on to my childhood because I never had one?"

Work is the clear priority for Huang and Holman. For now, the energy for romance and family life has been poured into creating Phantom Investigators. They spent Valentine's Day in the editing room, though Holman did give his wife flowers. They planned to go out to dinner, but as was true most every day this past year, by the time they got home from the studio all they could think about was sleep.

"We're looking forward to having our own time again, but we're not quite there yet," Huang says. "We barely have enough time to feed fish."

"Yeah," Holman says. "No time for kids. That's why we make kids' shows."

The directors of Phantom Investigators plan to incorporate their own worldview subtly into the show. For example, while the action is fast-paced and the protagonists are able to blast ghosts with a high-powered "Plasmo-Channeller," no one gets killed. The kids merely redirect negative energy with their weapons. Their first lesson: conflict resolution.

Take mean Mrs. Oglesby, the substitute teacher out to flush students down the toilet. As the kids investigate the situation, they find out Mrs. Oglesby really wanted to be a good teacher but never got the chance because her students always teased and tormented her. The team learns that people can become twisted by negative experiences in life, and that there can be reasons for a person's apparent maliciousness. With that understanding, the investigators don't kill her; instead, they apologize for the children who treated her badly. As a result, the ghost of Mrs. Oglesby can put down her plunger and rest in peace.

"If there's any message for kids here, it's to always look beyond what we might first perceive as the "truth' of any given situation," Holman says. "There is always a bigger picture, and that's where we usually find the cause of the anger, aggression, or resentment that is bothering us -- our demons and monsters."

What about something that's truly evil?

|

It's important to note that two separate but very real acts of evil briefly suspended production of Phantom Investigators. On Sept. 10 of last year, 33-year-old animator Billy Greene was shot and killed in front of his Emeryville apartment. There are no suspects and police are still investigating. The next day, of course, was Sept. 11.

"Everything blurred together -- society's violence, arbitrary insanity -- on a personal and global level in a one-two punch," Holman says. "But everyone wanted to keep on working. We could go home and worry, or try to make the world a better place. To keep doing this show, something special for kids, was the best thing we could think of."

Holman stops himself before he gets too existential about what is essentially a commercial TV show destined to help sell fast food. He shrugs those horrible memories off for the moment, then promises that Phantom Investigators will be, above all else, fun.

"I can jabber on about themes and ideas, but you won't get very far in kids' TV unless you make it entertaining," he says. "Hopefully, the ideas are what kids are left with after the adrenaline rush is over."

From his car on a gridlocked Los Angeles freeway, Sony's senior vice president of marketing breathlessly pitches the merits of Phantom Investigators on a crackling cell phone. "It has great story lines, boy/girl appeal, and great characters," David Palmer says, building up to his sure-fire tag line. "It's Scooby-Doo meets Nancy Drew!"

Apparently, the corporate marketer hasn't read the director's memo to the writing staff.

"Although a healthy sense of humor should run throughout this show, we'd prefer it was the ironic, dry, twisted, smart, witty, surrealistic kind," Holman instructed the writers in his note. "Scooby Doo-style obvious wacky hysterics is not the way to go."

So much for corporate/creative synergy. The show's creators don't waste much energy worrying what entertainment giant Sony and the WB network, owned by AOL Time Warner, say about the show. Holman and Huang are used to letting program executives express what they wish -- while quietly making sure that their own version is what's seen in the end.

|

"You won't believe the rules in national TV, especially for kids' shows," Holman says. "It's much harder to do anything today. I think Pee-wee Herman was the last bastion of weirdness. They really clamped down after that."

At times, the notes can make the directors cringe. One executive asked for some "Asian music" to accompany a scene in San Francisco's Chinatown.

"When they ask for an "Asian' score, we won't stand for some white man's idea of Asian culture, with violins and gongs. We'll compose a cool version with drum 'n' bass," Holman says. "Part of our job is to please the executives, and with a little ingenuity, we can -- without compromising our own ideas. If they hate our first idea, we don't just go change it to what they want. We come up with an alternative idea, which is really just the original idea in a new package."

Holman's casual attitude aside, it wasn't easy for him and Huang to verbalize the look and feel of this one-of-a-kind show in production conference calls to offices in Los Angeles.

"How do you tell a person what something will be like, when it's still mostly in your head? It's hard to convince people beyond, "No, it'll be really great.' It was frustrating -- especially when so few people have the vision to see potential without actually looking at a tape," Huang says. "I have to stand back all the time and ask myself, "Am I fighting this because they don't understand what I think, or are their objections right?' ... You definitely have to pick your battles."

Holman concurs.

"We can't get into an "us versus them' thing, because if we did, there wouldn't be a show. I know we can't go in with a totally nuts idea, because it'll never get on the air," he says. "We want to be as edgy as we can, but the difficulty in that is we have to play both their game and ours. And they have just one game: the bottom line."

No one will say how much it costs to make an episode of Phantom Investigators -- not its directors, not Sony, and not the WB. But Holman concedes it isn't cheap, considering the amount of time it takes not only to animate and film the puppets, but also to design and build each intricate set -- in addition to standard TV show expenses like story development and writing.

"People ask me, "How did you get Sony?' and I don't have an answer," Holman says with a look of amazement. "I know, it still blows me away. We're certainly not a safe bet."

The best explanation for two eccentric artists landing such a deal is Ilene Staple, the team's business partner. She represents Holman and Huang's interests in Los Angeles and is a hard-charging, savvy creature of the Hollywood machine. She knows exactly what to say, how to say it, and most important, whom to say it to.

"I'm the enabler more than anything else. I raise the money, make the deals, and protect Stephen and Josephine from the producers breathing down their necks. With me, battles are won before they even know about them," Staple says. "I love what I do, which lets them do their thing in a rarefied creative bubble. It's a dream situation."

Impressed with Holman's initial avant-garde work, Staple sought him out in the early 1990s at a Hollywood party. "I wanted to find my own Tim Burton," she recalls, referring to the dark and edgy director of Edward Scissorhands, "and there Stephen was, the quiet guy standing in the corner."

Huang joined the team soon after, and eventually married Holman. Neither liked the L.A. scene and both wanted to live and work in San Francisco. Staple was more than happy to stay behind and manage the business.

"Ilene is definitely a buffer who smoothes life out for us," Holman says. "She does the hard pitch at the meetings, so we can go down and be the kooky artists. The suits like that."

The duo's track record is also something executives like, which makes Staple's job easier.

"They are completely grounded artists. Not only are they creative, but they are very responsible. They're mindful of deadlines and budgets," Staple says. "They'll never make me look bad."

|

Another help was that Donna Freedman, the WB's executive vice president for children's programming, had previously worked at Nickelodeon, where Holman and Huang had made a splash on Life With Loopy. "Donna comes from the mindset of putting new networks on the map," Staple says. "There is no doubt this kind of show is a huge risk," one that could go a long way toward making or breaking a career.

Freedman supports Phantom Investigators as stop motion, convinced that its story and characters are strong enough to let its creators use their preferred medium.

"I wouldn't tell an artist they should only work in pastels or watercolors," she says. "Their unique style is an experiment for us, but if you don't take risks you don't find megahits."

How does she decide which show is worth the gamble? Freedman will only say, "A tremendous amount of scrutiny goes into what to program. I don't sleep at night."

Of course, executives use terms like "risky" and "innovative" only after a show is a proven hit. While it's still in production -- merely costing (rather than making) money -- those executives can be a headache for the directors.

"Anything we do that's crazy, freaky, or weird during the creative process makes them paranoid," Holman says. "But I have to remember they OK'd the show to begin with. They did take that risk, and I respect that."

It's a balancing act, as the directors try to please both the people who pay for the show and the kids who'll ultimately watch it. "Neither one is an easy job," Holman says. "I just know if we make an executive happy, it's a relief, but if we make a kid happy, it's a joy."

There are good reasons to film Phantom Investigators in San Francisco -- beyond the fact that the show's creators prefer living here. In fact, there's a long, rich history of stop-motion animation in the Bay Area. Gumby, that green putty TV icon, was brought to stop-motion life here. The pudgy Pillsbury Dough Boy (now computer-generated) began as a local stop-motion creation, too, as did those rambunctious Hershey's Kisses seen on TV commercials. Stop-motion feature films launched here include the famously spooky The Nightmare Before Christmas and the critically acclaimed children's fantasy James and the Giant Peach.

The talent pool of animators who can do the painstakingly tedious and demanding work of stop motion is small -- especially with so few outlets for this type of art. But with the Bay Area's history in the technique, more animators can be found living here than almost anywhere in the world. (Only England, home of the recent stop-motion hit Chicken Run, rivals San Francisco in its concentration of stop-motion artists.)

|

Pixar's style of computer-generated animation strives for realness, a humanlike imperfection that audiences can connect with. Stop-motion animators offer that desired sensibility, which is why Pixar wanted to train them on digital technology. Veterans like Tim Hittle, who helped make Gumby and the characters in Nightmare and Peach come alive, went on to master Pixar's computers for Toy Story 2 and A Bug's Life. But while he loved the product, he hated the process.

"Working from the keyboard is a big change when you're used to touching things," he says. "It's like trying to be a poet in a language you don't know."

Hittle and many like him missed their craft, and so they jumped at the chance to work on Phantom Investigators.

"The computer has a way of getting between you and your art," Holman says. "It can remove the soul."

Holman capitalized on that sentiment to secure his crew. "The big, computer-generated companies lay it on thick: better benefits, better pay, Häagen-Dazs bars in the freezer," he says. "But we're about lifestyle and craftsmanship. There is a genuine magic to stop motion. We're dealing with real light and shadows, using tactile materials like wood and paint to make things come alive. Sitting in front of the computer, glinting a million virtual hairs on dinosaur skin, is a grim prospect compared to our Santa's workshop."

Huang doesn't disagree with her husband's notions, but she takes a more pragmatic view. She realizes that the job standards Phantom Investigators' stop-motion animators enjoy could become distant luxuries if the show isn't picked up for another season.

"We've been very happy making our stuff, unto ourselves here in San Francisco," Huang says. "Who knows how long it will last? Next year, we could all be working for Pixar."

From sfweekly.com

Originally published by SF Weekly Mar 27, 2002

©2002 New Times, Inc. All rights reserved.