Focused Audio Meets Kelly Quan Research

The Evolution of Synchronizer Control Software

|

Author Jeff Roth at his Focused Audio studio in San Francisco |

It was not long ago that the methods and materials of music, film, and video sound technicians were unique and mutually exclusive. Only within the last few years has the combination of time code and affordable computer power allowed us to interweave these different formats. Having worked first in film, then music, and most recently in video sound, I have a great appreciation for the technology which has brought together these art forms. The result has been an infusion of creativity and experimentation in areas which haven’t seen technological change since the advent of magnetic recording and the invention of videotape.

In 1979, I was cutting mag tracks for a documentary entitled Word, Sound and Power. There I was at the flatbed, laying in "slug" (filler between sounds), splicing in my cue, re-splicing, labeling the trim of sound with a felt-tip marker, logging the trim and storing it, winding through my reel of mag looking for the next cue, marking it with grease pencil, marking the slug, splicing the slug, et., etc…Working on a six-plate machine, I could hear only two tracks simultaneously with picture, and when one track was my location recording of that sweet reggae music, the playback wow and flutter made me cringe. Around that same time, some very astute engineers were poring over papers and coming to an agreement, a standard for a time code which would assure them immortality–for this code’s future users would be so thankful for it, they would refer to the code by the name of the distinguished body which created the standard: SMPTE.

Time code, originally designed for video editing, has had an impact on every aspect of the recording industry. We use time code not only to link audio and video machines, but also synthesizers, multi-image projection systems, automated mixing and lighting boards, and more. In my experience, the most exciting application of time code has been the synchronization of multi-track audio machines with video machines. This achievement has turned the recording studio, designed just for music, into an electronic flatbed for film and video soundtrack design. Virtually overnight, the ways and means of creating soundtracks for video and film have been radically altered and expanded. After the code came the hardware.

The first synchronizer I had experimented with was the BTX 4500, vintage 1979. I modified my Otari 8-track and cabled it to the BTX. This first generation box was not "fully intelligent"–it would synchronize tape machines within three seconds, but the slave machine was not capable of chasing to the master’s location. It was therefore necessary to manually park both transports close to the same SMPTE number, and then start them simultaneously while hitting "enable" on the 4500. While this sounds laborious by today’s standards, it seemed like a miracle then. Synchronization without sprocket holes, seven tracks of audio on one piece of tape–truly amazing. I later lightened my burden by getting the BTX 4600 keyboard to control the synchronizer. This unit gave "go to’s," autolocated to any time code number, and allowed me to program record ins and outs and remotely "enable" the synchronizers. It remembered and executed 35 events, and triggered my half-track with a relay closure at a pre-programmed time code number: for that time, a very impressive box. Encouraged by the success of some very complex experiments, I bought another 4500, a BTX 4100 time code generator, BTX 4200 reader, and an Otari MTR-10.

Seduced by the combination of multi-track and image, Focused Audio moved into audio-for-video specialization. When it came time to upgrade the studio last year, I fell prey to the insidious "duck bonding syndrome." Like those little feathered creatures, I attached myself to the first things I saw as I emerged from the electronic editing egg. I bought an Otari MX-70 and a pair of BTX (now Cipher Digital) Shadows.

|

As anyone who has picked up a recent audio or video trade magazine knows, the synchronizer market is jumping right now. I held off buying the BTX-designed Softtouch controller for my Shadow synchronizers at that time, even though I thought it was the most advanced design, because I was anxious to see some of the IBM-based software programs that were coming out for this purpose. A computer-based system obviously would allow for fantastic memory capabilities, the ability to load in and out various kinds of lists, and unlimited potential for growth and system evolution. While investigating some of these IBM-based programs, I was assisted by Dave VanHoy of Sound Genesis (now with AIC). Dave introduced me to Kelly Quan, the San Francisco-based software writer and designer of the Otari synchronizer for the MTR-90. The timing of this meeting was fortuitous for both of us–I needed a controller for my new system, and Kelly needed a working audio-for-video studio to test his software development.

A year ago, when I first saw a demo of Kelly’s software program, it consisted of one screen and was not (at that time) capable of all the functions of a Softouch. I made my decision to take a chance and invest in this early version of the software, and a computer to run it, based on what I saw in the early stages of development, and the vision of what the system could evolve into.

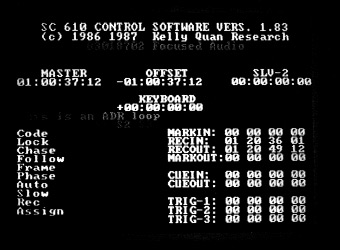

The first software version I received consisted of one color screen which displayed all synchronizer status modes, constant time code read-outs for the master transport and a chosen slave transport, and the running offset between the master and chosen slave. The display of the edit information was logical and easily understood. "Record ins" and "outs" refer to the master machine, in my case the VTR, and the multi-track, which in my setup is slave #1 and usually running at a zero offset with the master. "Mark in" and "mark out" allow you to set different parameters for the actual start and stop points of the master, which is helpful in ADR applications and music overdubbing when the talent needs additional lead-in time before the actual record point. The "cue in" and "cue out" registers refer to the time code locations on the designated source machine; in my application, slave #2 is the 2-track timecoded source machine. A third slave machine can be accommodated. While there were no memory storage capabilities in that version of the program, the simple fact that all the information I possibly could need was there simultaneously on a color monitor was a great aid, and an advance over most available systems.

The first new addition to the software came when I needed to assemble some non-time coded 1/4-inch tapes. Working with producer Claire Schoen on Desde el Exilio (Voices of Exile) for National Public Radio, our elements consisted of interviews, ambient sounds, and translation overlays. Since Ms. Schoen’s tapes all were prepared with leader when she came to Focused, I asked Kelly to incorporate a trigger start command into his software. Using the relay closure in one of the Shadows, and a new display which could be toggled on and off, the new version of the software would trigger any one of three slaves at a specific master time code number. It also included a programmable key for determining a trigger delay time, if one were necessary. With the time readout on the MTR-10, it is a simple task to back off the cue one second and mark the tape for accurate re-cueing. With one second stored in the trigger delay, the cued sound comes up right on target, without having to perform any time code calculations.

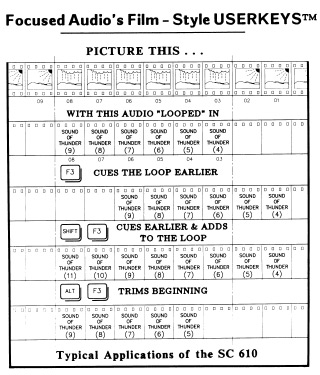

When user-programmable keys were added to the software, the operating speed took a quantum leap forward. A user key can record many individual key strokes and play them back as programmed when needed. Available in the user keys’ memory are 3000 key strokes, which can be spread over an incredible 56 user keys in any combination. With this many keys available, it’s possible to create a permanent key for rarely used functions. The first keys I programmed simply moved a cue forward or back by whatever value I put into the keyboard display. This seemingly simple task combined about a dozen keyboard strokes into one. While working with David Brown on A Question of Power, his documentary on the anti-nuclear movement which aired nationally on PBS in ’86, I developed 12 user keys to perform specifically film-oriented adjustments to a particular cue. Since David’s background was in film, this gave us a quick, accurate basis for conceptualizing how we intended to change the cue relative to picture. Focused engineer Marian Wallace drew a graphic chart, illustrating the effect of each user key as if the sound were being manipulated on a flatbed editing machine. In the current software version, the user keys are stored on floppy disk, so each operator can carry and load in their own key assignments wherever they work.

|

The Kelly Quan synchronizer program's screen display includes master, slave and offset status readouts, as well as record and mark in/out points. |

The next software version I received contained an EDL memory and a "scratch-pad" memory. The EDL memory was storable to floppy and could hold 99 edits. I got into the habit of hitting the "store loop" key and assigning a number to each edit, writing down that number on my cue sheet. During work on Not All Parents are Straight, Kevin White’s documentary which will air nationally on PBS this year, we put this new feature to work. Composer Frank Harris continually gave us new orchestrations or remixes of his score, which he created on a Synclavier. To audition a new cue, we simply recalled the original edit number, entered the time code number of the new music mix into "cue in," and pressed "begin." Going back to change an edit was quick and painless.

As the software stands now, the EDL holds 999 edits, which can be printed out; a CMX EDL can be loaded in and the audio edits extracted; and there is a new screen for EDL list management which lets you insert, delete, move, or scroll through edits. You also have the ability to add a notation to each edit, which will be displayed on the normal screen and the EDL screen when you scroll to that particular edit number. The edit notes print out with the EDL list.

In response to complaints about not knowing the current EDL memory position available at any given time, Kelly devised an elegantly simple way to assign an EDL number to an edit. The same "enter" key used to write a user key now automatically enters the edit information and comment into the next open EDL slot–with one key stroke. This eliminates up to five key strokes previously necessary ("shift," "store loop," "O", "O", "1"). The EDL also can be used in an auto-assembly mode.

Two more memories available for storage and print-out are the "scratch-pad" and the "log." Right now, both are in use on G-Rex, a video feature by producers Rob Seares and Paul Bassis. With a running time of an hour and 40 minutes broken down into five reels, there are many cues and source tapes to access. Normally, this would call for a complex looping system; and still much time would be spent searching. The "log" consists of a screen with the running master time code displayed in the center. When you hit the carriage return key, the code freezes and allows a message to be typed in; hitting return again stores the time code number and messages, and starts the code rolling again. This feature also can be used to log audio tapes and print out time code numbers and messages. When G-Rex director Ursi Reynolds flew in from Oregon to oversee the soundtrack building, we called up the "log" function and proceeded through the entire feature, entering time code location notes for music, fx, ADR, Foley, and mix notes. I then printed out hard copies for us. This "log" became the master spotting list from which we compiled library effects, and it was our check list in building tracks and mixing.

The "scratchpad" stores time code numbers in memory locations 00 through 99. Once we compiled our music, narration, and effects on 1/4-inch reels with center-track time code, we logged them into the scratchpad memory. I always code each 1/4-inch reel with a different time code hour designation for easy identification, and include that number in the reel’s computer ID name. Going through each reel one time, we grabbed the starting time code number of each cue with one key stroke, hit "store," and then the appropriate memory location. After this, we stored to floppy and printed out the log of each 1/4-inch tape, giving them names like "rex#1.scr," etc… If we needed to access effect #32 of fx reel #3, I would simply put up the 1/4-inch tape, load the memory of that reel into the program, hit "recall," "32," and the 2-track parked at that effect. If we wanted to hear it in sync to picture, I hit "store," "cue in," and "begin." I no longer had to concern myself with the actual time code location of the sound, because the computer knew it. This is extremely helpful when using Focused’s library of 1/4-inch tapes of common fx like "wind," "traffic," exterior ambiance," etc…

A computer virgin at the start of this collaboration, I found it exhilarating to witness the amount of raw computer power which can be harnessed for a very specific purpose. Kelly Quan’s Audio Editing System puts this power to work, providing a sophisticated, flexible, yet extremely affordable system.

Technology has changed soundtrack production for film from a slow, labor-intensive activity into one that’s fast and equipment-intensive. Reactions to this new way of working go to the extremes in both directions. The tactile experience of manipulating mag tracks, cutting away at the raw material like a sculpture with a stone cannot be duplicated in the realm of electronic audio editing. The aesthetic implications of this change in process have yet to be determined. For video soundtrack production, the implications are clear–the tools necessary for audio to fulfill its expanded role in the digital, hi-fi, laser age of consumer electronics are now available.

MIX Magazine, April 1987

Copyright 1987 by Mix Publications. Reprinted with the permission of the publishers.